If you find yourself feeling limited by the camera in your phone, chances are you’ve thought about buying a better camera. Something with a bigger sensor for better low-light performance, or shallower depth of field. Maybe the ability to switch lenses for different situations.

Very likely, you’ve taken a look at the field of Digital Single-Lens Reflex (DSLR) cameras available, clutched your head in agony, and wondered where to start. This article does not discuss or recommend specific cameras, but rather gives you a bit of insight into how these cameras are marketed, and what their strengths and weaknesses tend to be. Using this knowledge, you will be able to look at what’s on offer and have some understanding of what the different models are for, and why you might want them.

The Broad Categories

DSLR cameras come in three general types: Consumer, Prosumer, and Professional. You can tell these apart right away by their suggested retail prices or street prices. Generally speaking, the consumer cameras are comparatively inexpensive — right now, that translates to about $400-800 for a kit with the camera, a lens, and a couple accessories like a bag or an inexpensive tripod. The prosumer cameras cost more, usually from about $800 up to about $2000, sometimes for a kit, but usually for just the camera body with no lenses. The professional cameras pick up around $2000 and go up, up up. These price values may not be valid any more as you read this article, so keep in mind this was late 2017. Unless the market changes dramatically, though, something like these three classes will continue being available for at least a few more years.

Consumer cameras are generally more lightly built, and have fewer features than the more-expensive bodies, but not a lot fewer. In fact, the consumer cameras are frequently so featureful that it simply doesn’t make sense to progress beyond that level. A key element of this is that you will see practically no difference in image quality between the different levels of cameras. There are some exceptions, but for most photographers, a current consumer-level camera is a fantastic tool that will do everything you want it to. Keep that in mind as you look around: the image quality from a $400 SLR is about the same as the image quality from a $4000 SLR. (To be strictly accurate, they’re not the same, and you do get slightly better image quality from the higher quality cameras, but certainly not 10x better images.)

Prosumer cameras are a blend of the consumer and professional cameras, as their name implies. They’re intended for people who are really serious about photography, and who are willing to drop some serious cash on their hobby. They will generally have heavier construction to take more abuse, and more features that make taking good photos easier. The image quality will bump up a little bit, but not by much. What the prosumer cameras really get you is a refinement of features. Things like more autofocus points (which makes focus easier, or more likely to work in low light, or easier to customize to your exact shooting situation), or smarter exposure measurement (which means the photo is more likely to come out like you want, instead of with some element horribly over- or under-exposed). Frequently, the prosumer models will offer easier control of more aspects of the camera — fewer menus to dig through, and more buttons and knobs that just do a thing like switch modes, or control exposure, or set autofocus modes or points.

Professional cameras are cameras with eye-watering prices and a long list of features that, if you’re earnestly reading this article, will make little to no sense to you. That’s ok, it’d be a terrible waste of money to step from a cellphone camera to a professional DSLR. If you’re absolutely rolling in cash and are only willing to have the best, this is the category to aim for, but things get trickier here. The market has recently started specializing a bit more, and that’s most apparent in the pro cameras: cameras with very high pixel counts for landscape work that don’t do well in a studio, cameras that are super-optimized for sports photography, cameras that will only shoot in black and white, etc. There are still many generalist cameras at this level, but by the time you’re looking here, you should already know what you want and why you want it, and my little article should be completely redundant to you. Professional cameras will have vast swaths of features you never use, and which may make operating the camera more confusing than a consumer or prosumer model.

Let Me Re-emphasize: Image Quality

The most important point of this article, the thing I want you to take away from it, is that

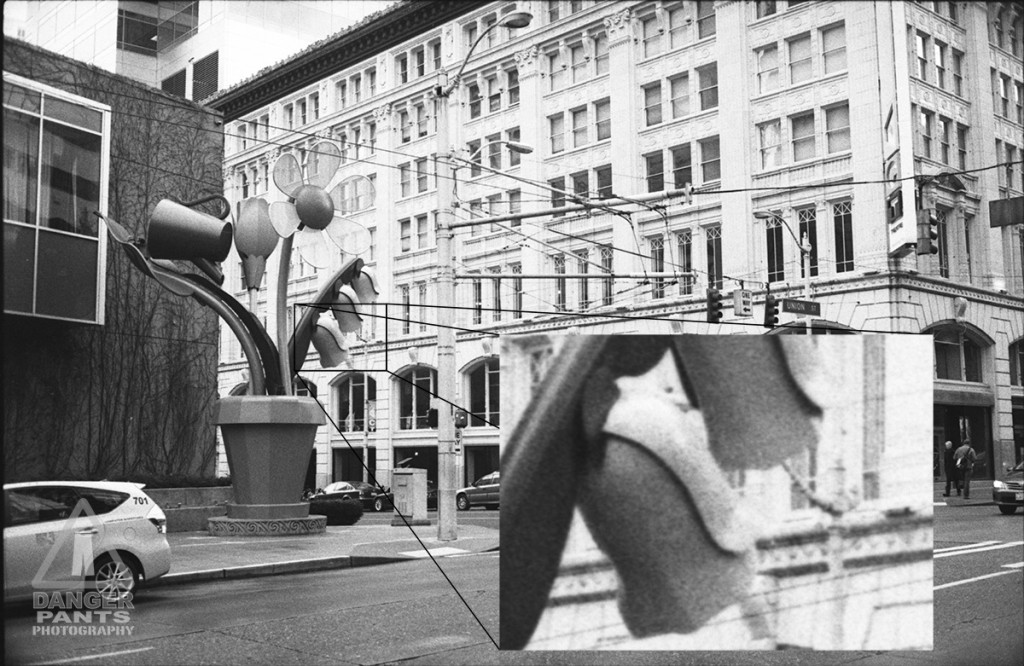

You Can Make A Good Picture With Any Camera

From a cellphone (within reason, there are some terrible phone cameras) to the most expensive medium-format $50,000 digital camera, they’re all capable of turning out really good photos. The image quality from the least expensive modern DSLR is many times better than film for a given ISO (light sensitivity). The cost of the camera (as long as we’re discussing modern DSLRs) does not determine how good the picture that appears on your screen will be. The more you pay for the camera, the easier it will be to make that excellent photo, but they’ll all make an image you could put on the cover of National Geographic if you do your part.

A Word on Megapixels

It’s lessened in recent years (thankfully), but there was once the War of the Megapixels. Every manufacturer loudly touted how many megapixels their camera was able to capture, and legions of people bought the camera that had the highest number. Thing is, this is a silly number to obsess over. A 1200×800 pixel image is huge online, and most pictures you see on Facebook or Instagram are fewer pixels than that. A 1200×800 image is just under 1 megapixel. If you’re shooting photos to post online, and your camera shoots more than 1 MP (most shoot in the 16-24 MP range these days; even cellphones routinely shoot 8-16 MP now), you’re set, 16-24 times over. A 5×7 print image is a bit over 3 MP at 300 dots per inch (DPI).

There are a number of arguments for More Megapixels, and they are quite valid (I’ve upgraded my camera specifically to get more pixels, in recent memory). The big one is for print. If you want to make a photo into an 11×17 poster, which has been my use-case, you’ll want to print that photo at 300 DPI (or even more), and that means a 16 MP camera is the smallest you can use without scaling the image (which can easily destroy image quality). Another excellent use of Moar Pixels™ is that you can crop your image and still have a very high-quality image left over.

The trade-off for having more pixels is that the image quality tends to suffer as you pack more sensors onto a chip. To some extent technology is solving that, as demonstrated by the very high-MP cellphone cameras that are actually quite good.

Megapixels should not be your overriding concern unless you know for sure you’ll need them. Any modern DSLR will meet your needs the vast majority of the time.

A Word on Brands

As of this writing, and for many years already, there are only two brands of DSLR that are considered the main contenders: Nikon and Canon. Each brand has its boosters and its detractors, and people can get very heated about it, but the real truth is that they’re both really good. They have different strengths and weaknesses, and it’s worth figuring out what you want to do, and which brand aligns with your interests, but either one is likely to be a good system for you. I strongly recommend that you not just shop online for your first DSLR, but actually go to a camera store and play with them. You may find that one simply Makes Sense™ to you and the other one doesn’t. That happened with me, and I ended up in the Canon side of the house, but I can clearly see that Nikon also makes fantastic cameras.

The one thing to keep in mind is that your progression, should you get excited enough about photography to progress beyond your first DSLR (and it’s ok if you don’t!) is that you’ll find yourself collecting lenses. Once you do that, you tend to be committed. Nikon lenses don’t fit on Canon bodies and vice versa. There are adapters out there, but it’s not the same, and you shouldn’t expect the same performance. So if you start down one brand’s path, you’ll probably stay on it unless you dig losing a lot of money on lenses when you switch.

Lenses are More Important

It seems a bit non-sensical at first, but it’s true: lenses are more important than cameras. Lens technology is stable, without much churn. You can buy a lens from 20 years ago that will still work on a modern Nikon or Canon body, and will produce stellar images (sometimes literally, if you’re doing astrophotography). The lens you buy today will almost certainly work on the new body that Nikon or Canon come out with in 20 years. DSLRs aren’t really going away as a class of camera, but the camera tech changes yearly. You will buy a new body in 2-3 years if you get serious about it, and then probably every 2-3 years after that.

To be sure, there are advances in lenses all the time, with faster and quieter focus motors, and better coatings on the glass, and interesting new designs popping up. But because of the rate of change, and the fantastic quality already present in the lenses, consider your DSLR body to be relatively disposable compared to the lenses.

This means that when you’re considering the purchase of your first DSLR, it actually makes sense to spend as much or more on the lens as you do on the camera. This idea subverts the marketing of these cameras, since they promise to be all-singing and all-dancing, but a camera body is useless without a quality lens. The kit lenses are usually decent, but suffer, sometimes badly, from lightweight construction. They’ll take good photos, but don’t expect them to last long. Plus, more so than the camera bodies, you will see a real improvement in image quality by using a higher quality lens.

Also, Mirrorless

When you’re looking at a new camera, it’s well worth looking at mirrorless designs as well. These cameras have really taken off in the last decade, and they’re improving rapidly. This also requires a shift in terms: Canon in particular isn’t much of a contender here, Nikon is more present, and Sony is off the charts from what I’ve seen. Olympus and Panasonic and Fujifilm are all making strong showings. I’m not as familiar with this market, so I can’t offer any real advice, but I’ll say that I have an Olympus OM-D E-M5, which is a ~5 year old Micro Four-Thirds camera, and still really like it as a walking-around camera.

Mirrorless cameras offer good value, rapidly improving picture quality, and rival or beat their SLR competitors in many ways. They have the advantage of being smaller and lighter, which is a real boon when you have to carry the thing for an entire day. I have the impression there’s not as much of a consumer/prosumer/professional divide, though that may be developing as the market matures.

Last time I looked, the biggest negative point for mirrorless cameras was that the selection of lenses was small compared to what’s available for the SLRs. The market simply hasn’t been around for long enough. There are excellent lenses available, but the breadth of focal lengths and maximum apertures is lacking.

Consider Used

Used cameras (and used lenses) represent a ridiculously good value. I mentioned above how you’re probably going to upgrade your camera body every few years? So does everyone else. This means that there is a robust and underpriced used-camera market out there. For example, I bought a new 1st-generation Canon 7D when it had been on the market for about a year, for $1200. I sold it to a friend four years later for $400, but I wouldn’t have gotten much more than that on Ebay. My first DSLR was a Canon XTi, which I got for around $600 in a kit, and sold about five years later for $50 to a friend (it was worth more than that, probably $100-150, but even so). A 3-year-old prosumer camera will set you back the same amount as a new consumer camera, or even less. If you can stomach not owning the latest and greatest, used cameras are fantastic value for the money.

Online Resources

For the first and last word on camera reviews (including any used DSLR or lens you might come across), go to DPReview.com

For very high-quality used cameras and lenses at better-than-Ebay prices, check out KEH

For all the new gear, and some of the used gear, meander on over to B&H Photo and Video and Adorama Camera